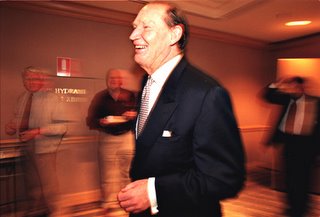

Kerry Packer dies at 68

THE LAST time Kerry Packer died, 15 years ago, he quickly took the opportunity to pooh-pooh the existence of an afterlife.

"I've been on the other side and let me tell you, son, there's f---ing nothing there," he was fond of saying.

It was a statement redolent of the media baron's forthright approach to life and his laconic sense of humour. Given he had been clinically dead for eight minutes after suffering a massive heart attack while playing polo, his recovery was hailed as a medical miracle and testament to his lust of life. Just a week later, on his discharge from hospital, he leapt from his car and threatened to punch a journalist he believed was intruding on his privacy.

Kerry Francis Bullmore Packer died aged 68 on Monday evening at home with his family. He had a long history of heart disease and kidney ailments and received a kidney transplant donated by Nicholas Ross, a long-time friend and helicopter pilot.

Packer was Australia's richest man, with an estimated personal wealth of $6.9 billion.

The country's biggest media baron, he controlled the Nine Network, a string of magazines and maintained an enduring interest in owning his family's longtime publishing rival, John Fairfax.

As the former chairman of Publishing and Broadcasting Ltd, Packer controlled a number of influential publications, including The Australian Women's Weekly, The Bulletin, Australian Business, Cleo, Woman's Day, Dolly, Mode, and Harpers Bazaar.

Packer elicited conflicting emotions from those he dealt with. To some he was the most respected businessman of his time, to others the most feared; some associates loved and others loathed his hard-nosed approach to business.

A similar attitude existed among his employees. Sometimes described as a feudal lord, at times impossible and overbearing, he could also be extraordinarily generous and indulgent - particularly with those who had served the company for a long time.

Born on December 17, 1937, the second son of Sir Frank Packer, he was educated at Cranbrook School in Sydney and Geelong Grammar in Victoria. He married Ros Weedon in 1963 and was father to two adult children, Gretel and James.

Packer inherited control of one of the country's biggest media empires and never shrank from the challenge or responsibility that ownership entailed. He was the third generation of his family to enter the media world. His grandfather, Robert Clyde Packer, was described by The Times of London, as a successful Sydney journalist who became a newspaper executive and one of the founders of Smith's Weekly and the Daily Guardian.

But it was Kerry's father, Sir Frank Packer, who created the empire. A bombastic man who in 1967 advocated the "killing of 500 Negroes" as a cure to stop black revolutionary violence in the US, Frank Packer started The Australian Women's Weekly and transformed The Daily Telegraph into one of Sydney's leading newspapers. He was also responsible for bringing television into the homes of Australians with his Channel Nine in 1956.

An arch-conservative, Sir Frank unashamedly used his media outlets to ram home his political views and actively championed the federal Liberal-Country Party coalition in election campaigns.

A one-time heavyweight boxing champion, polo devotee and keen sailor, Sir Frank had two sons, Clyde and Kerry. Clyde was always expected to take control of the business but, after falling out publicly with his father, he went into state politics before leaving for the United States. Until that time Kerry had been thought of as nothing more than an idle playboy. But in 1972 he found himself thrust into the limelight and bought Clyde's share of the business. Two years later his father died and he took the helm of Consolidated Press, the family company.

Much has been written about the poor relationship between Frank Packer and his sons - an experience that, despite his gruff exterior, Kerry Packer was keen to avoid with his offspring. In a 1984 interview on a rare return to Australia, Clyde Packer remarked of his younger brother: "He's a clone of my father, only he's much better at personal relationships. He's much softer."

In later years Kerry Packer was to remark that his father was a just and fair man. But there is ample anecdotal evidence that his father was an authoritarian who was never particularly close to anyone, including his sons.

Both sons were inducted into the media business and on their father's strict instructions were not to be treated favourably by other employees. Both were subjected to constant derision and public humiliation by their father in the office, leading one of his lieutenants to ask whether Clyde was "a saint or an imbecile" for smiling throughout such dressings down.

In particular, the young Kerry was forced to perform the most menial tasks at The Daily Telegraph and Women's Weekly including cleaning the ink from the printing cylinders - tasks for which he showed little enthusiasm and for which he reportedly resented his father.

Clyde rebelled by resigning as managing director of Channel Nine and briefly adopting an alternative lifestyle, getting around town in a kaftan and mixing with the emerging counter-culture before moving overseas.

Kerry accepted the challenges thrust upon him by his father and the responsibilities of running a big corporation. But unlike his father he nurtured a strong bond with his two children. Fiercely protective and proud of his children, Kerry Packer on occasion was moved to defend them physically from incursions by the media and other outsiders.

Packer was an unashamed devotee of television, and his Nine Network dominated the airwaves with a combination of news, current affairs and sports telecasts.

Long before many of his international rivals, Packer, a passionate sportsman, identified business opportunities that sport could offer television. He proposed an international golf circuit. But it was his incursion into the staid world of international cricket administration that created an uproar and later revolutionised and reinvigorated the game.

In 1976, with colour television being introduced into Australia, Packer bid for the exclusive Australian rights to televise Test cricket matches.

But he was beaten by the ABC, despite offering more than seven times the Government network's bid. Compared with other sports, cricketers were poorly paid. So when a rival Packer competition, World Series Cricket, was launched the following year, many leading players rushed to join, splitting the game and throwing the establishment into crisis.

Rather than white flannels, the new teams were sometimes dressed in colourful "pyjamas" and played shortened versions of the traditional five-day Test matches. After winning a resounding victory in the High Court against the cricket establishment, Packer's rival tournament faced a rocky start. Access to traditional venues was denied, audiences shunned the games and sponsors were disappointed. But in its second year Australians warmed to the new set-up, particularly when night matches were introduced.

In 1979 a truce was called between the warring factions. Full-length Test matches and limited over games were played under the auspices of the cricket establishment. Not surprisingly, Packer's Channel Nine gained exclusive rights.

Besides cricket, the Nine Network devoted itself to other sports broadcasts and frequently set technical benchmarks against which international networks measured themselves.

Not content to be an armchair devotee, Packer became seriously involved in sport. At school he had played cricket in the First XI and rugby in the First XV and, like his father, was a boxing champion.

Although he had a flair for all ball sports, he was by no means considered brilliant, and earned his place in the teams through persistence and determination.

He sailed on yachts in the Sydney to Hobart race, was an accomplished golfer and in later years - despite his size - became an adept polo player. He compensated for shortcomings in natural ability with a fierce competitive streak which earned him widespread admiration from his competitors.

A poor school student, the young Kerry found himself isolated and friendless, particularly at Geelong Grammar, where his fellow pupils looked down on his family as being nouveau riche. He suffered from dyslexia - a condition which went undiagnosed for many years - and was forced to repeat a year in primary school and again in high school. He would describe himself as "academically stupid, a dolt", but his later penchant for business and strategic investment contradicts that assessment.

To counteract his poor scholastic performance he turned into something of a thug at school - bullying classmates and behaving belligerently towards teachers. As in primary school, he concentrated on his sporting prowess.

Although thrown into the business world, initially by Clyde's departure and then his father's death a short time later, Kerry Packer proved he was no dolt. He had strong ideas on television, in particular, and on the future of magazines.

Before his father's death, he launched the ground-breaking Cleo magazine for women, against the advice of his father and their advertising agency. It was to prove a runaway success.

He learnt three important lessons from his father: be loyal to your allies, tough with your adversaries, and not to care too much about other people's opinions.

While he stuck to that philosophy, Kerry Packer was extremely hurt by damaging allegations that arose out of the royal commission into the Painters and Dockers Union in 1984. Documents leaked from the commission were published in the now defunct Fairfax weekly The National Times, identifying a central figure, codenamed the Goanna, involved in tax evasion, fraud, pornography, drug importation and murder.

A fortnight after they were made public, Packer identified himself as the Goanna and then proceeded to demolish each accusation. In time, all were to be proven false. But Packer harboured deep resentment over the allegations and his treatment by the commission and the media.

A formidable businessman, he was a feared negotiator in business deals. He pulled off his most famous coup in January 1987 when he sold his Nine Network to Alan Bond for $1.05 billion. Desperate to reduce debt, Bond and a coterie of executives had flown to Sydney in their private jet to sell their interest in Perth's Channel Nine. Once at Packer's Park Street headquarters, however, Packer convinced Bond that the pair should negotiate without advisers. When he finally emerged, an elated Bond confided to his shocked entourage that rather than sell Perth, he had bought the entire national network.

"You only get one Alan Bond in your lifetime, and I've had mine," Packer later quipped. Three years later he bought back the station - with an expanded network - for little more than $200 million in one of the deals of the decade. In 1983 he had shown similar business acumen in privatising Consolidated Press. He used $110 million of the company's money to buy assets valued at at least double that.

During the latter part of the 1980s Packer teamed up with two friends, the British financier Jimmy Goldsmith and the banker Jacob Rothschild, to launch a $28 billion bid for British American Tobacco, which if successful would have been the second biggest takeover the world had seen. The three also launched an $880 million bid for the food group Rank Hovis McDougall. Both bids failed, and Packer lost an estimated $80 million.

In 1987 he acquired a strategic interest in his rival publisher John Fairfax. He sold the stake to Warwick Fairfax during his takeover bid for the company for a handsome profit and bought Fairfax's magazines for the bargain price of $220 million.

His interest in Fairfax was rekindled three years later, after Fairfax plunged into receivership. Packer became an integral partner in the Tourang consortium that included the Canadian publisher Conrad Black. Although Packer quit the consortium before Tourang took control of Fairfax, he built a key stake in Fairfax several years later. When he died he still had an interest in the group through a separately listed trust.

Packer survived a number of serious illnesses, including childhood polio, the removal of a cancerous kidney and a diseased gall bladder in 1986, and diabetes.

But his heart attack in 1990 prompted him to begin an overhaul of his business empire, paving the way for James to take control. A drastic cost-cutting program that shed many superfluous businesses was followed by a stockmarket listing for a new company, Publishing and Broadcasting, which was controlled by the Packer-owned Consolidated Press.

James formally took the job as managing director of PBL in 1996 with the US-born Brian Powers as chairman, although it was widely acknowledged that Packer maintained an active interest in the day-to-day running of the business. Powers later became chairman of John Fairfax, and James took over as chairman of PBL.

Although he kept a watchful eye on his son's business activities and his advice was often sought, Kerry gave James the freedom to take the business in new directions.

It was a decision that delivered enormous profits as James was instrumental in building up PBL's gaming division, which now accounts for about half the group's earnings. Last year James spearheaded the successful acquisition of Perth's Burswood casino, despite opposition from his father. He is now looking at picking up gaming assets in Asia.

James also moved PBL and the family owned Conspress into new technology ventures in telecommunications and the internet, such as the jobs website Seek and ninemsn, a joint venture with Microsoft.

But there were some failures, including the spectacular collapse of the telecommunications company One.Tel in 2001, which prompted Kerry to once again become more engaged with the day-to-day running of PBL. While James's pride may have been hurt, the family's wealth was left largely unscathed.

Kerry Packer's property purchases reflected his business philosophy of domination. The amalgamation of a number of properties around his Bellevue Hill mansion, Cairnton, extended the family estate to an estimated 11,100 square metres. His property at Scone, Ellerston, became one of the world's best polo facilities after a $10 million revamp in the late 1980s. In 1989 he bought the 37.6-hectare Great House Farm in West Sussex, England, which he also transformed into a polo estate.

When in London, Packer usually took five luxury suites at the Savoy. He would often stay for the entire northern hemisphere polo season and conduct business from the hotel.

Along with polo, which took him to tournaments in Europe and South America, his other great passion was gambling.

An habitue of Las Vegas and London casinos, he was considered the world's biggest gambler, and would occasionally win or lose as much as $20 million in a single sitting of his favourite game, blackjack.

For the owners of Caesar's Palace or the Las Vegas Hilton - two of his favourite establishments - a Packer win could severely dent annual returns, while a Packer loss could help the house to a bumper profit for the year.

He once was so annoyed by the boasting of a millionaire gambling beside him that he proposed they flip a coin for the $200 million the American said he was worth. The offer was declined.

His gambling interest prompted Packer to make a serious but unsuccessful tilt for control of the Sydney casino in 1994, while his company became a large investor in the Crown Casino in Melbourne and in Hudson Conway, the company of his friend Lloyd Williams, which ran the casino. When Hudson Conway ran into difficulties, James Packer, in his first big deal at the helm of PBL, bought out Hudson Conway and took control of Crown.

Meanwhile, Kerry's love of blackjack and his spectacular wins and losses provided endless fodder for gossip columns. He also loved gambling on horse races and once famously made a killing at the Melbourne Cup when he and Lloyd Williams reputedly picked up more than $10 million.

After his 1990 health scare Packer lost an enormous amount of weight and gave up smoking, a habit he readily admitted was an addiction. But he took up cigarettes again and gradually replaced his weight.

Although a big drinker in his youth, he gave up alcohol after being involved in a serious car accident as a young man in which another person died.

Packer's kidney complaint eventually deteriorated to the point where he was kept alive by dialysis until kidney surgery in the US in 1998. That operation failed to ensure his health, and a kidney transplant was seen as the only alternative.

In recent years his health problems continued. Besides diabetes, he had a melanoma removed from an ear, experienced heart problems and returned to hospital complaining of tightness in the chest, shortness of breath and loss of appetite. Although he continued to take a close interest in the running of his businesses, recent public appearances indicated considerable weight loss and ill-health.

He is survived by Ros and his children Gretel (born 1965) and James (born 1967).